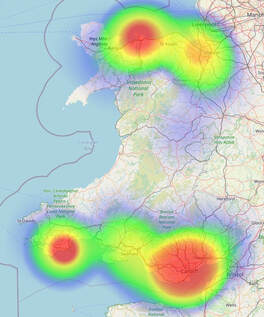

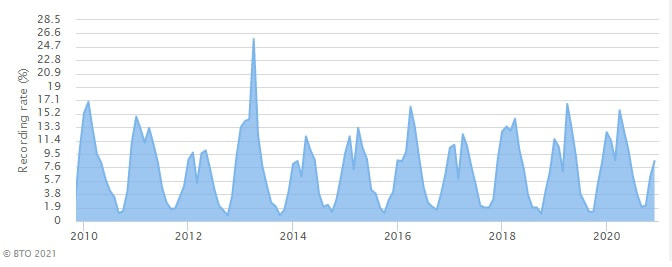

'Heatmap' of Blackcaps reported in Wales to BirdTrack* between 1 January and 15 March, and 15 November and 31 December 2019. 'Heatmap' of Blackcaps reported in Wales to BirdTrack* between 1 January and 15 March, and 15 November and 31 December 2019. The first few days of January saw a remarkable five different species of warbler in North Wales, a family of birds usually associated with long days of summer. Our one regular resident warbler, Cetti’s Warbler, lives around wetlands, primarily on Anglesey, and Chiffchaffs and Blackcaps occur in small numbers across the region. A Yellow-browed Warbler and Lesser Whitethroat on Anglesey are more unseasonal, however. Blackcaps now occur regularly in Britain in winter. Hugh Linn, who lives near Rossett, Wrexham, currently has seven in his garden. Four are males, of which one is moulting out the ginger cap that it’s had since it fledged from its nest last summer. He remembers seeing his first winter Blackcap when he was Rector of Eccleston, on the outskirts of Chester, in the 1980s: “We had put out some fat with other edible offerings for our garden birds and we were very surprised to spot a male Blackcap tucking in, as in those days we had only encountered them as summer visitors”. Blackcaps are found in around one in seven British gardens that participate in the BTO Garden Birdwatch project, and slightly more frequently in gardens of Welsh participants. Blackcaps are generally found along the coast, with numbers usually peaking in January or February. Their presence here in winter has been noticed since the 1960s, coinciding with the start of growth in people putting food out for wild birds. Numbers really grew during the 1980s, and have been fairly stable since the mid-1990s. Garden feeding has certainly helped Blackcaps to survive the second part of the winter, once the autumn berry crop is exhausted. A survey of BTO Garden Birdwatch participants found that 70% of Blackcaps fed on fat-based foods, such as suet balls, and 35% on sunflower seeds. In summer, they eat small insects, hence those that breed here migrate to the more temperate Mediterranean, although some travel farther and cross the Sahara. Summer residents do sometimes stay beyond late October, when autumn migration is over. In the early 20th century, North Wales naturalist Herbert Forrest reported a Blackcap being “pugnacious” to other birds in a Porthmadog garden, and it has earned a bit of a feisty reputation for defending feeders from other birds, especially Blue Tits. When people noticed more Blackcaps in winter, in the 1970s and ‘80s, many assumed that these were birds that had not migrated south. I remember attending a lecture by German ornithologist Dr Peter Berthold at the 1993 BTO Conference, at which he explained his orientation studies of Blackcaps captured in central Europe during the summer. In autumn, some of these showed a strong tendency to move to the northwest corner of their aviary and he was convinced that these were the source of Blackcaps wintering in Britain. In order to try and prove his theory, he got permission to catch a small number of wintering Blackcaps in Somerset, which then bred in captivity in his aviaries near Lake Constance on the Swiss/German border. Berthold and his colleagues showed that the following autumn, the chicks from those British birds also attempted to move northwest, back towards Britain, just as he predicted. I remember being staggered when I heard his talk, which was before any of the modern technology that enables us to track birds. What was most astonishing was the speed at which the change had happened. Evolutionary biology had traditionally told us that it took hundreds, if not thousands, of years for such a radical change to occur in migration, but Berthold showed that it could happen in just a few dozen generations of birds if the conditions were favourable. Garden bird feeding in Britain has provided those conditions. Berthold subsequently proved that the direction of travel was set by the birds’ genes. The first birds to make the journey, perhaps by accident, returned to their breeding areas earlier in spring than those coming from farther south, so they paired up with each other and thus the genetic selection for migration to Britain was strengthened. Fast-forward almost 30 years and technology has added more detail to those studies in the 1980s. Tiny, ultra-lightweight geolocators, which record day length, were attached to more than 600 Blackcaps across continental Europe during the breeding season, and to over 130 wintering in Britain. When 100 of these birds were recaught, the data stored in the geolocators enabled scientists to back-calculate the position of the birds on most days in the intervening period. This showed that the trait for wintering in Britain is not restricted to the area of the original southern German studies, but extends from northeast Spain through France, and east through central Europe as far as the Polish border with Ukraine, a distance of over 2,000km (see the map in Fig. 1d of this paper). The same study found that British-wintering Blackcaps arrived back in their European breeding area 10 days earlier than those that travelled south. It is quite possible that Blackcaps in adjacent territories in Europe head to different places for the winter, but while they live close to each other, they are effectively divided by that 10 days, which means they are evolving separately.

It is rare for scientists to be able to study such a dramatic change within a lifetime’s work, and there is still much to discover about Blackcaps wintering in Britain. The highest densities are in southwest Britain, and over the last three winters over 600 have been colour-ringed in Cornwall as part of a study by the BTO, Oxford and Exeter Universities, so if you do see a Blackcap in your garden, check its legs for plastic rings, and send details of the combination to [email protected]. In the meantime, it will be interesting to see how many Blackcaps are reported in the RSPB Big Garden Birdwatch, which takes place on 29-31 January. Besides Blackcaps, there have been plenty of other winter birds seen this week. Several Firecrests are wintering in Gloddaeth Woods near Penrhyn Bay, where a Water Pipit remains on nearby fields and another is on Llandudno’s North Wales golf course. Three Great Northern Divers are off Dinas Dinlle and one flew over Bangor Pier on Monday, and two Surf Scoters were off Llanddulas at the weekend. Two Long-tailed Ducks were in Y Foryd and another at Cors Erddreiniog until the lake froze at the weekend. Long-stayers include a Black Redstart in Beaumaris, Rose-coloured Starling at Amlwch Port, Iceland Gull at Rhyl’s Brickfields Pond and Snow Buntings on Holyhead breakwater. *BirdTrack is a partnership between the BTO, the RSPB, Birdwatch Ireland, the Scottish Ornithologists' Club and the Welsh Ornithological Society. Participation is free and open to all.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Bird notesA weekly update of bird sightings and news from North Wales, published in The Daily Post every Thursday. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed