|

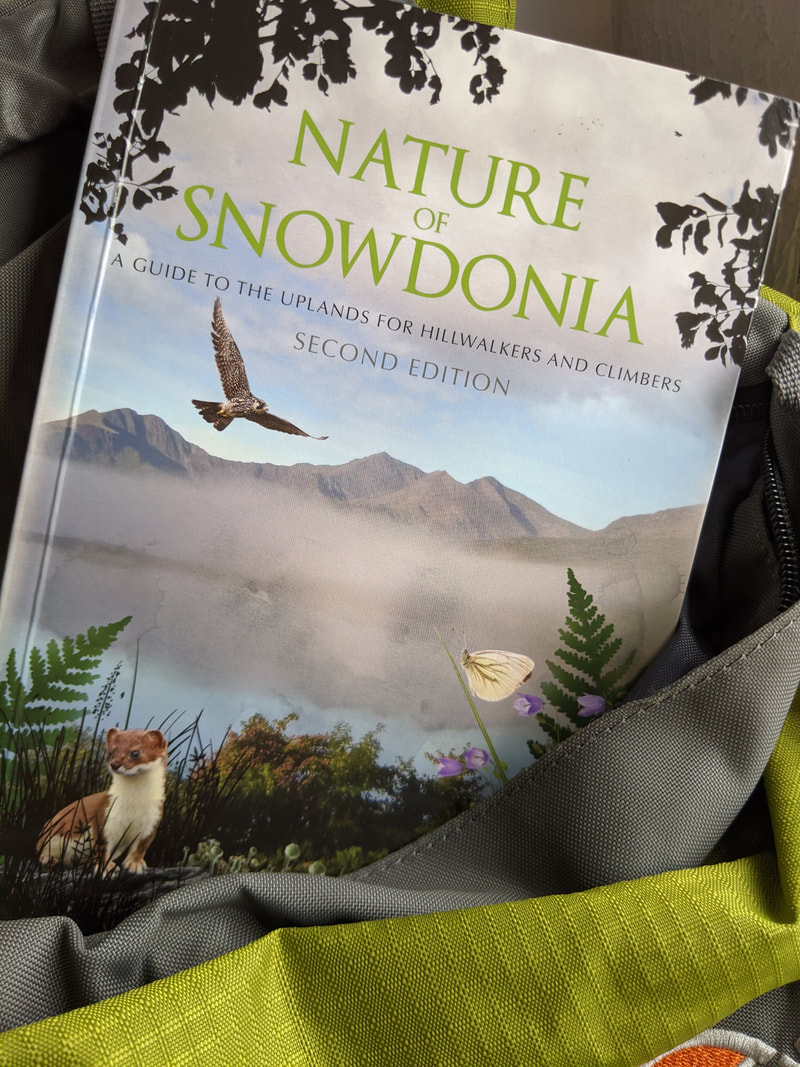

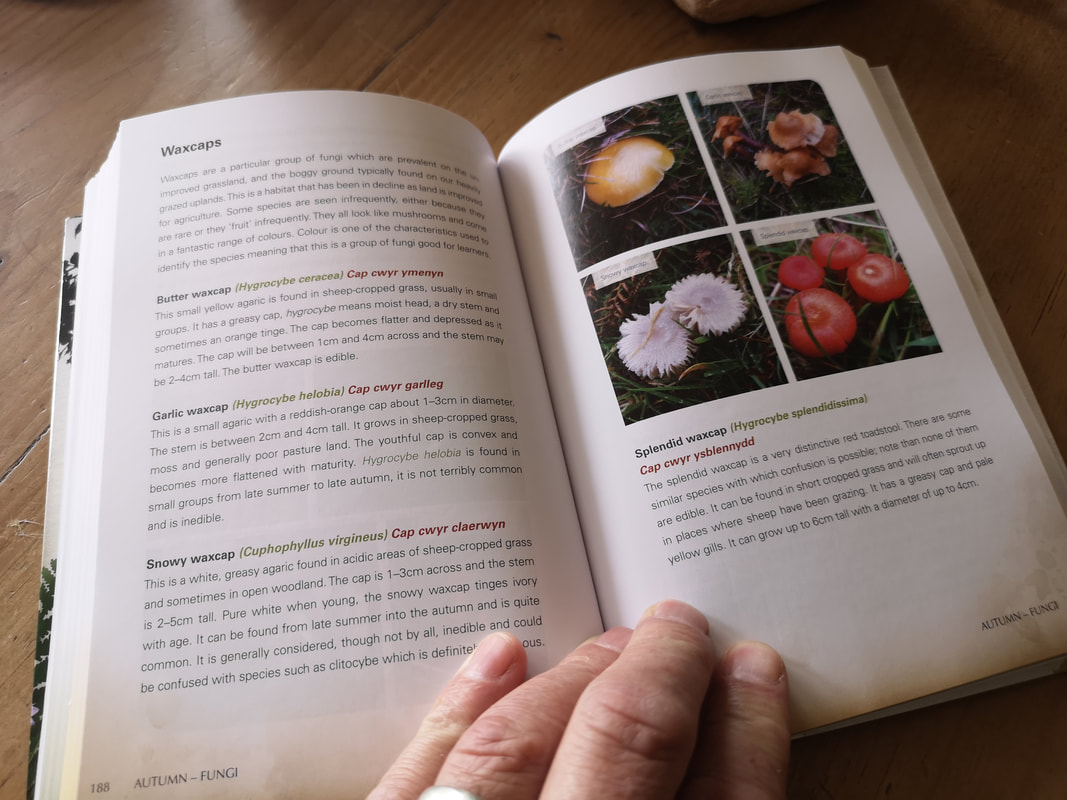

Launching a new book about the outdoors of North Wales in the middle of lockdown isn’t what author Mike Raine would have chosen, but it will give readers time to dream of future visits to the mountains. Nature of Snowdonia is not, you might be surprised to know, a book written for naturalists; that said, everyone will learn something new and ought to have it within easy reach whatever your reason for being in the hills or valleys. Mike is, at heart, a hillwalker and climber, who has worked as a geography teacher and an outdoor instructor since the 1980s. Living in the Conwy Valley, until recently he worked at Plas-y-Brenin, the National Outdoor Centre near Capel Curig and wrote the first edition of the book a decade ago, but it has long been out of print. This second edition has been extensively rewritten, with hundreds of new photographs. “I’ve met a lot more people in the last ten years, experts from whom I’ve picked up a lot of knowledge,” he says. “My skill is to teach and communicate, and from running hundreds of courses I know what a generalist audience wants. When they’re out, they ask “what’s that plant?, why does that rock formation look like that?, why is that sheep-fold there?” Nature of Snowdonia tries to answer many of those questions. “I spent two years taking photographs of what I saw when out in North Wales, so the book features what anyone might typically expect to see,” explains Mike. It takes a seasonal approach to narrow down the choices, especially of the many plants that grow in Snowdonia, but this is not purely an identification guide. It describes not just where you’d expect to find wildlife but also why, the origins of their names, and in the case of plants how people have used them for medicine or clothing. People may buy Nature of Snowdonia as a one-stop guide to upland wildlife, but it does something that I think is unique in a pocket guide. It explains. There is a section on ‘Invaders’ that describes the problems caused by Rhododendron and Himalayan Balsam in the National Park. A chapter on farming describes how it has shaped the Snowdonia we see and the consequences for people and wildlife. It features some of the archaeology a visitor might find, from Neolithic tombs to the slate industry and wartime tank-traps. It even mentions some of the legends of the area, such as The Afanc and the dragons of Dinas Emrys.  Geology is a particular passion of the author, but he sees the difficulty with accessing information from experts. “Geologists have to start with the big picture,” he says, “it’s how you understand the landscape. But when you’re not an expert and come across a boulder embedded with quartz, you want to know what it is and why it’s there, so I’ve flipped geology on its head to make that the starting point”. The scope of the book is an extension of Mike’s own philosophy: “anyone working or walking in the outdoors should be an ambassador for it,” he says. “You should understand its different users and uses. That’s my personal mission, especially when training those who will lead others. I want people to be aware of the issues that have shaped our landscape in the past, today and will determine its future”. It’s billed as “a guide to the uplands for hillwalkers and climbers” but farmers, naturalists and householders who live in the area should value it too. When we can go walking again, it’s going to be a fixture in my rucksack. Nature of Snowdonia by Mike Raine is published by Pesda Press, costs £15.99 and is available by mail order from mikeraine.co.uk/shop.

0 Comments

Dusky Warbler at Wylfa Head (Lewi Burgess) Dusky Warbler at Wylfa Head (Lewi Burgess) The firebreak lockdown has again demonstrated that there are plenty of birds on our doorsteps, so keep an ear open during half-term walks this week. The rarest find was a Dusky Warbler at Wylfa Head on Anglesey. This songbird breeds in central Siberia and should now be arriving on its wintering grounds in southeast Asia. There are only half a dozen Welsh records, although this was the second reported in North Wales this autumn. Not so rare, but perhaps a smarter-looking bird, was a Pallas’s Warbler, which has also travelled here from east of the Ural Mountains. It is even tinier, at just 7 grammes it weighs less than a pound coin. Its yellow head and wing markings have earned it the moniker ‘the seven striped sprite’. One was on the Great Orme on Sunday, darting around the canopy searching for tiny insects almost 32 years to the day since the site’s first. There have been a couple of others on the Orme in the intervening years, but the thrill of finding one was as good as the first, said finder Marc Hughes. Others have found good birds even closer to home, such as a Turtle Dove in a Bala garden and a Black Redstart in Porthmadog’s Garth Road, and Snow Buntings were at Holyhead’s Soldier’s Point and over Waunfawr. Yellow-browed Warblers were at Nant-y-Gama above Penrhyn Bay and in Breakwater Country Park, and a Woodlark was near Carmel Head over the weekend. A Short-eared Owl has been hunting over saltmarsh west of Llanfairfechan, a Firecrest is on Bangor Mountain, and a Lapland Bunting flew over Roman Camp. The first Great Grey Shrike of autumn was at Pennal, overlooking the Dyfi estuary. A few summer migrants remain, including a Wheatear at Anglesey’s Cemlyn Bay and several Swallows around the region. Three sounds dominated my walk in the woods at the weekend. First were the numerous Mistle Thrushes, which gave away their presence with their football-rattle like call. Other thrushes included large numbers of Redwings and Fieldfares that had just arrived from Scandinavia. The Mistle Thrushes are more local, family groups that have spent late summer feeding on bilberries in the hills and are now coming into the valleys to raid the Rowan trees hanging heavy with bright red berries. Second was the hum from every bunch of Ivy, its umbrella-like yellow flowers providing an autumn lifeline for the bees and flies still on the wing. Third was the raucous screech of the Jays – its Welsh name Sgrech y Coed says much more about the sound of autumn than its English name (which originates from the old French).

Student birders on Bangor Mountain monitored some impressive visible migration at the weekend as part of the Global Birding initiative, which brought together 30,000 birdwatchers in 120 countries. Their highlights were three Hawfinches, Yellow-browed Warbler, Lapland Bunting, Ring Ouzel and a Firecrest, which contributed to a global total of 6,910 species seen in a single weekend. Monday saw thousands of Chaffinches and small numbers of Bramblings moving along the North Wales coast. Hawfinches were on the Great Orme and at Caerhun, and one colour-ringed in the Conwy Valley two winters ago was photographed in Lincolnshire recently, presumably returning from its breeding area in Scandinavia. The Great Orme also hosted several Snow Buntings, Lapland Buntings and Ring Ouzels, and a Firecrest was ringed there last week. Other Firecrests were at Holyhead’s Breakwater Country Park and Porth Meudwy. A Wood Sandpiper was unseasonally late at Traeth Dulas on Anglesey, a Dusky Warbler was at Uwchmynydd and a Barred Warbler at Tonfanau last week. It’s been a week for birders to listen out for the disyllabic ‘tsw-eee’ sound of Yellow-browed Warblers, an autumn migrant that has rapidly changed its status in western Europe. I remember seeing one on the Great Orme in the late 1980s when it was a real rarity, but now we expect to see small numbers in North Wales every year, and thousands across Britain. They breed each summer in forests around the most eastern margin of Europe, in the foothills of Russia’s Ural Mountains.

Yellow-browed Warblers can turn up in any patch of coastal scrub or woodland. Over the weekend there were several on Bardsey, and singles near Pwllheli, at Holyhead’s Breakwater Country Park and Uwchmynydd on Llŷn. Most winter in southeast Asia, so are these westbound movements all doomed to die? Well, perhaps not. Winter records in Iberia and North Africa have also increased and it may be that these tiny birds travel all the way back to Siberia in spring. Although this has yet to be proven, one was seen in November 2018 in the same Andalucían copse where it had been ringed the previous winter. It had presumably been to Russia and back in the meantime. Although the second week of October is the peak for sightings in Wales, I’m sure there are more to be found as winds turn easterly again from Wednesday. Other sightings in recent days include a Great Northern Diver and Leach’s Petrel in Bull Bay, Whooper Swan off Aber Ogwen and a Velvet Scoter off the Great Orme. There were two Lapland Buntings at Uwchmynydd and two Spotted Redshanks at RSPB Conwy, where several Great White Egrets remain, with more egrets near Denbigh, on Bardsey and from Porthmadog Cob. There are also Firecrests at Porth Neigwl, Porth Meudwy and RSPB Conwy. I'll be answering your questions about birds in Wales on the Bywyd Gwyllt Glaslyn Wildlife Facebook page on Tuesday 13 October at 7pm. Hope to hear from you there! The combination of easterly winds and heavy rain made birdwatching difficult at the weekend, but there were interesting sightings for those who made the effort. The rarest birds in the region were on Bardsey: a Siberian Lesser Whitethroat, and an Eastern Yellow Wagtail, that is only the second ever seen in Wales - check the Bird Observatory blog for 3 October to read more, including how to identify the wagtail's call.

Mainland highlights include Rose-coloured Starlings at Morfa Nefyn and Bull Bay, Lapland Bunting at Llanystumdwy, three Great White Egrets at Porthmadog Cob and six at RSPB Conwy. Yellow-browed Warblers were at Porth Meudwy, Bangor and on the Great Orme. The east coast saw the pick of the sightings, which included a trio of Russian thrushes in Scotland: White’s, Siberian and Eye-browed, while a Masked Shrike near Hartlepool and Two-barred Warbler in Northumberland also originated to the east. A Tennessee Warbler dropped onto Yell in Shetland from North America, illustrating how almost anything is possible during autumn migration. Wales’ summer migrants are arriving in their tropical or southern winter quarters now, including thousands of terns that left our coast just a few weeks ago. The North Wales Wildlife Trust wardens at Cemlyn recently wrapped up their season with a webinar to report on a successful year for the tern colony. Almost 2000 Sandwich Tern nests was slightly down on the peak of a few years ago, but nonetheless amounts to almost 2% of the global population. The 750 pairs of Arctic Terns and 250 pairs of Common Terns were their highest ever totals, and over 1000 non-breeding terns added to the spectacle. The increase occurred following the abandonment of The Skerries colony, illustrating the importance of having alternative places that these seabirds can feel safe if they need a Plan B. Common Terns previously ringed on The Skerries also bred at RSPB Hodbarrow in Cumbria and Dalkey Island, close to Dun Laoghaire port in Ireland. |

Bird notesA weekly update of bird sightings and news from North Wales, published in The Daily Post every Thursday. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed