|

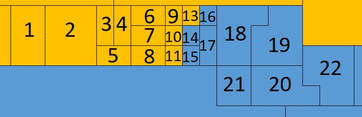

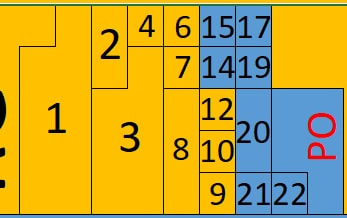

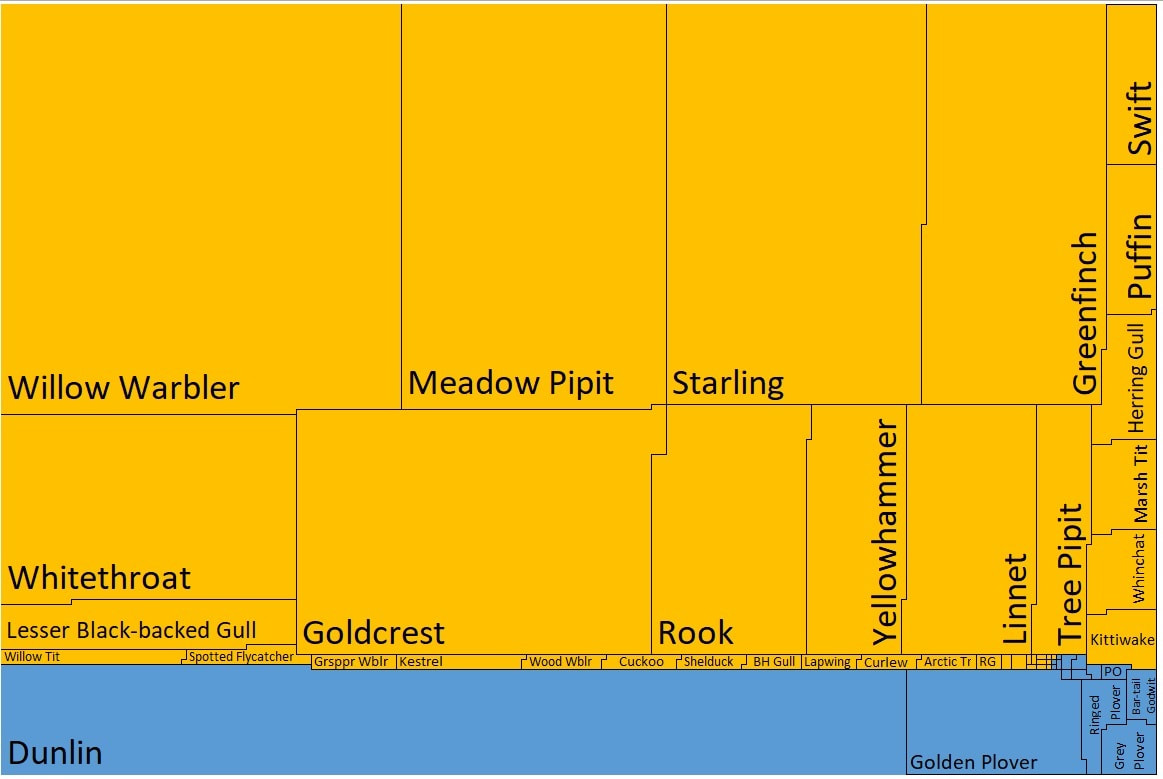

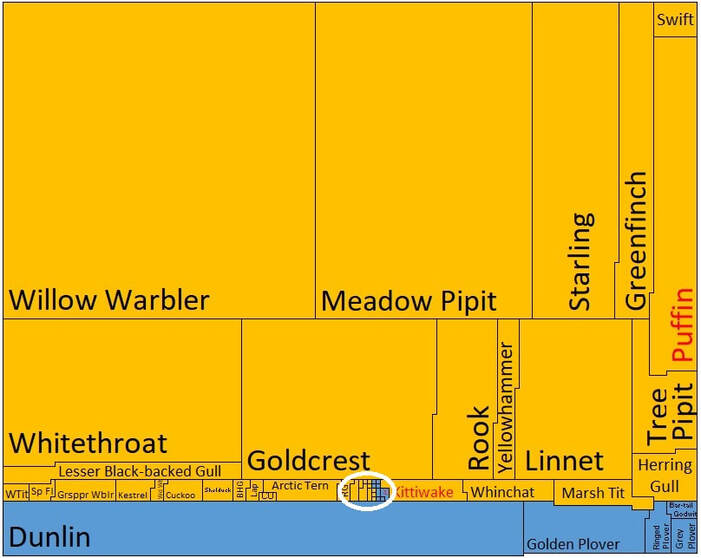

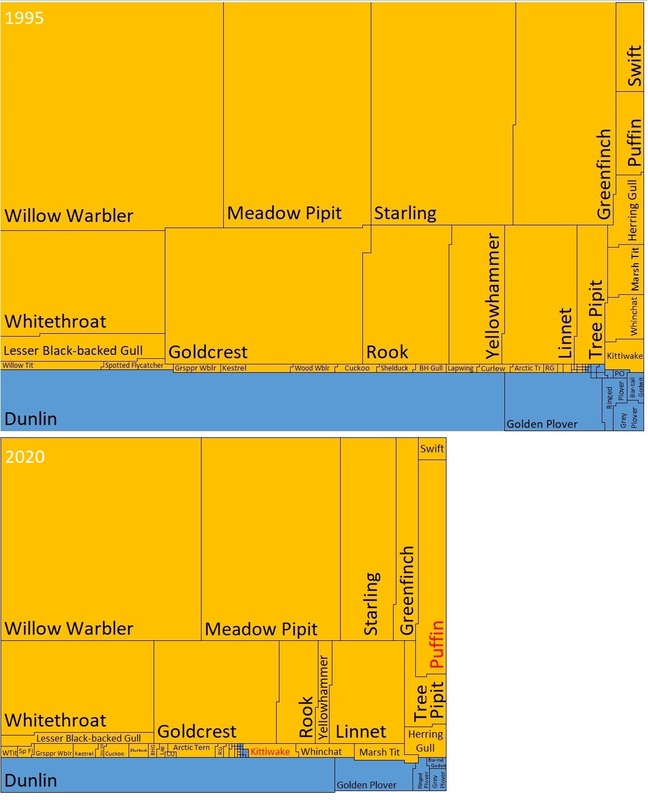

Earlier this month, a suite of organisations published the fourth edition of Birds of Conservation Concern Wales, which resulted in updated Red, Amber and Green lists (see this page to download the assessment). Having been involved as a volunteer collecting the sort of data that informs these periodic reviews, editor of the annual Welsh Bird Report published by the Welsh Ornithological Society and a co-author of previous UK and Wales assessments, I wasn't shocked by the results because I'd seen them coming. But I should be. We've almost come to expect each update will be worse than the last, because we see and hear these changes with our own eyes and ears. But it's only inevitable if society allows it to be. Those of us who care about nature should be livid every day about the lengthening red list and the declining abundance of birds we assumed would always be part of Welsh life. Behind each component of the Red List is an unfolding tragedy ...usually of birds failing to rear enough young to replace themselves, although in some cases it's about survival after fledging or during the part of life spent outside Wales. For a few, it's likely to be 'short-stopping' whereby some individuals no longer travel to Wales because conditions closer to their breeding area are, for now, suitable for them to spend the winter there. The charts below shows each species according to its population in 1995 and 2020 (or the nearest available date for which I could find data), enabling me to picture the numbers in relative terms. It's not the perfect way to present the information, as some populations numbered hundreds of thousands and others just a few dozen, and the count units are not always the same, as breeding birds are generally counted in pairs and non-breeding birds as individuals. It's also worth remembering that not all species declined by >50% during this 25 year period; some qualified for the Red List because of declines in abundance over a longer period, others because of a >50% contraction in their distribution or because they are at risk of global extinction. KEY: orange = breeding population (usually pairs), blue = non-breeding population (individuals). Golden Plover appears twice because declines in both its (different) breeding and non-breeding populations qualified it for the Red List. RG=Red Grouse, PO=Pochard.  Some populations are so small that they don't show up well on this chart, so those in the white ring above are detailed here. 1. Ring Ouzel, 2. Tree Sparrow, 3. Black Grouse, 4. Merlin, 5. Turtle Dove, 6. Golden Plover, 7. Grey Partridge, 8. Little Tern, 9. Redshank, 10. Woodcock, 11. Yellow Wagtail, 12. Hen Harrier, 13. Lesser Spotted Woodpecker, 14. Long-tailed Duck, 15. Slavonian Grebe, 16. Bewick's Swan, 17. Purple Sandpiper, 18. Velvet Scoter, 19. Balearic Shearwater, 20. Red-breasted Merganser, 21. White-fronted Goose, 22. Leach's Petrel. Breeding populations <20 pairs are not shown: Roseate Tern, Bittern, Corncrake, Corn Bunting and Honey-buzzard. Non-breeding populations <20 individuals are not shown: Little Auk. And here is the equivalent chart for 2020. Species marked in red qualify as they are globally threatened. WdWb=Wood Warbler, BHG=Black-headed Gull, Lap=Lapwing, CU=Curlew, RG=Red Grouse.  Again, the species from the tiny boxes are listed below: 1. Ring Ouzel, 2. Tree Sparrow, 3. Black Grouse, 4. Merlin, 6. Golden Plover, 7. Grey Partridge, 8. Little Tern, 9. Redshank, 10. Woodcock, 12. Hen Harrier, 13. Lesser Spotted Woodpecker, 14. Long-tailed Duck, 15. Slavonian Grebe, 17. Purple Sandpiper, 19. Balearic Shearwater, 20. Red-breasted Merganser, 21. White-fronted Goose, 22. Leach's Petrel. Breeding populations <20 pairs are not shown: Roseate Tern, Bittern, Corn Bunting (extinct), Corncrake (extinct), Honey-buzzard, Turtle Dove, Yellow Wagtail and Lesser Spotted Woodpecker. Non-breeding populations <20 individuals are not shown Little Auk, Velvet Scoter and Bewick's Swan. Lost forever? The extinction of Corn Bunting as a regular breeding species during the last quarter century, preceded by Corncrake and with Turtle Dove heading in the same direction, is a particular shocker. The first two no longer qualify as Birds of Conservation Concern in Wales because they are now so rare as not to meet the minimum threshold. That does not mean we should write them off, especially as people are working hard to save them from extinction in other parts of the UK. Global extinction risk Nine species in the latest assessment are globally-threatened, none of which were in 1995. This criteria automatically qualifies them for the Welsh Red List, even if their numbers are increasing here. All are declining here too, with the welcome exception of Puffin, whose breeding numbers have grown in the last 25 years albeit they remain far lower than a century ago. The square must shrink no further Instinctively we know that populations of most of these species are falling. That is why many are on the Red List. It is birds of the wider countryside, such as Meadow Pipit, Starling, Greenfinch, Goldcrest, Rook, Swift, Yellowhammer, whose shrinking abdundance is most evident when you see the two charts together. These birds take up less space on the lower chart because they take up less space in the countryside, their collective sound diminishing by more than 40% in just one human generation. The 25 years between these two charts is nothing in the lifetime of the planet. If we had the numbers to go back to 1970, to 1945 or pretty much any other date is history, the contrast in size of these boxes would be even greater. Shifting baseline syndrome is a real risk in limiting our ambition to the state of nature in our own memory. It's not just a question of looking back, but using what has been learned to look forwards, to restore habitats and recover bird populations. 2023 must be an important year for nature in Wales. Commitments made by the UK Government at the recent UN Biodiversity Conference COP in Montreal and by Welsh Government in its five-year Programme for Government must be realised. The Agriculture Bill before the Senedd and the promises resulting from the 'Biodiversity Deep Dive' must reverse the shrinking square. And proper resources and energy need to be invested in Natural Resources Wales and the parts of government with responsibility for achieving change. So, as the new year dawns, let's hope - no, let's ensure - that those in power do the right things to grow that square. And those who can, let's get out and count birds - if you don't already, make it your resolution to participate in BTO survey from 2023. Population estimates sourced from a variety of surveys and papers, including Hughes et al. (2020), Pritchard et al. (2021) and calculated from the Wetland Bird Survey and Breeding Bird Survey, using UK trends where no Wales-specific trends were available.

Hughes, J., Spence, I. and Gillings, S. 2020. Estimating the sizes of breeding populations of birds in Wales. Birds in Wales 17(1): 56-67. Pritchard, R., Hughes, J., Spence, I., Haycock, B., and Brenchley, A. 2021. The Birds of Wales/Adar Cymru. Liverpool University Press.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Bird notesA weekly update of bird sightings and news from North Wales, published in The Daily Post every Thursday. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed